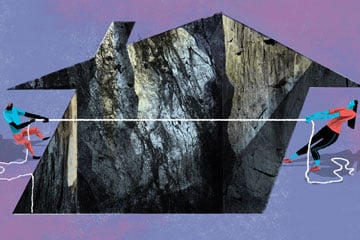

While venturing out into the real estate market to purchase a new home may seem like a constructive way to start life anew after a marital split, a series of landmines await the unwary divorced person.

Buying a home in the midst of a divorce can become a legal landmine.

While venturing out into the real estate market to purchase a new home may seem like a constructive way to start life anew after a marital split, a series of landmines await the unwary divorced person. Until all the issues between the two splitting parties are resolved and they have a signed separation agreement in hand, a separating spouse could face some serious repercussions when buying another home too quickly.

The legal risks could be driven or further complicated by state of mind. Divorce and separation are often so emotionally charged that common sense, which might normally be in great supply, could be elusive for some, says St. Catharines, Ont. family lawyer Sharon Silbert. A splitting spouse may rush into a real estate deal without realizing the implications their family law case might later have.

What looks like a simple real estate transaction could quickly deteriorate into a messy web of complications. “I think it’s important for us to remember that individuals who are going through a separation or divorce are for the most part dealing with an extremely high level of stress and change in their lives and there are many decisions they need to make, sometimes in a relatively short period of time,” she says. “I think it’s incumbent on us as professionals to do what we can to educate our clients about the kinds of decisions they may need to make while they’re going through the separation process and the importance of taking things one step at a time and making sure that the live issues in their family law matter are settled before they’re incurring any new financial obligations.”

The purchaser may not have been forewarned by the real estate agent or even the banker when they sought pre-approval for a mortgage that a separation agreement is required before the mortgage can be approved. They can find themselves high and dry at the 11th hour if they’ve signed a binding agreement only to discover that they can’t access the cash to close the deal.

Don Travers, a real estate lawyer with Paquette Travers in Kitchener, Ont., has seen varying twists of the same problem.

“They just assume they’re going to get 50 per cent of the matrimonial home,” he says. “They go to buy another home and then they find out that their spouse isn’t agreeable to that 50-50 and, if they’re not agreeable, then the sale proceeds have to be held in trust until it’s all sorted out, which means that the person can’t complete the purchase of their home.

“And then, of course, all of a sudden they’re in a conundrum: ‘Well I’m going to get sued by the seller if I don’t complete and yet I think it is unequitable what my spouse is suggesting all of a sudden.’”

At that point, they may be forced to choose between some unsavoury options: risk being sued or concede to terms that were previously unacceptable just to nail down that separation agreement in time to get the financing approved for the house purchase. If the terms include taking a smaller cut of the house proceeds, it could mean having to find someone else, like a family member, to go on title to secure the additional financing required for the purchase.

Problems might well be avoided by the lawyer handling the real estate deal. Finding out the individual’s marital situation and what bearing that might have on the transaction will make a difference if those questions are asked. Although, that, too, isn’t always failsafe, says Regina, Sask. lawyer Yens Pedersen, because much of the conveyancing work is often done by legal staff.

“In a lot of cases, a lawyer will simply glance at a file, not really paying a lot of attention to it,” he says. “Sometimes, because of that, there’s a danger that the lawyer handling the file might not actually be apprised” of the fact that the file should be handled differently.

There is also a risk that the other spouse will later make a claim on the property purchased after the disintegration of the relationship if that agreement is not crystalized, adds Pedersen. Some couples, for instance, simply separate, live apart and continue on with their lives independently. If one buys a house, the other could argue that it’s part of the divisible family property.

In Saskatchewan, he points out, the default division date is actually the date that legal proceedings are commenced, not the date of separation. So, if they haven’t dealt with the separation of property, everything that they’ve each acquired, even after their split, could well end up on the table as divisible family property.

In Johnston v. Johnston Estate, a couple living in a house in Vancouver worth $40,000 in 1971 separated but never divorced and they had no separation agreement. “Because they were still married, there was no limitation period that kicks in,” which would normally be two years from the time of separation for those that aren’t married or two years from the date of divorce for married couples, says Lauren Read, who practises family law and real estate law with BTM Lawyers LLP in Port Moody, B.C. Decades later, in 2015, the husband sought half the current value of the house, which by this time had skyrocketed in value to $1.2 million, and he was successful.

Because in B.C. family law value of property is based on the fair market value at date of trial or date of the actual agreement, there is a risk for those who don’t resolve the issues in a timely matter that the values will fluctuate.

While seeking a claim on the property 44 years later is unusual, there can be other challenges for the spouse who wants to retain the family property.

With through-the-roof house values in Toronto and Vancouver, many are house rich and money poor, so an individual might be challenged when buying out their partner and seeking financing on their own. “That creates some interesting issues for people and some creative solutions for us to figure out how to keep them in the property and perhaps how to refinance and possibly to handle things in a different way,” says Read.

Parents or family members might be summoned to go on title to help secure the necessary financing. Again, that separation agreement is crucial. In British Columbia, the property transfer tax exemption is required, which, at one per cent for the first $200,000 and two per cent for the remainder, can be a huge savings.

There is also a significant difference in how property is viewed for common law couples versus married couples. In a common law relationship, if one spouse is not on title, even if they’ve been in the relationship for more than three years and have a child through the relationship, they have no rights on the property, whereas the married spouse does. The common law spouse will have to make a claim on the property.

If that single person on title emerges from the relationship and sells the house, that could potentially expose the purchaser to legal action, says Jacqueline Boucher, who practises family and estates law with Cox & Palmer in Saint John, N.B. “You could end up in a situation where the former spouse who was left out of the transaction brought the purchasers into litigation to establish their claim.”

What is more likely to happen, she says, is that spouse will file a lis pendens, or certificate of pending litigation, which is registered on title. That provides a warning to potential purchasers that there may be litigation on the property.

There is also a remedy available to the spouse who wants to sell the house and get out of the relationship when the other party isn’t agreeable. It’s a situation Travers has seen with young couples, particularly women who feel they’re carrying the financial burden. They have the option of seeking an action for partition, which forces the unwilling party to agree to the sale of the house.

“It always seems to be the young woman who’s trapped in this situation where she wants to get out, she wants to sell and the boyfriend is not agreeable. And then we threaten the partition action and then we get [it] resolved,” he says.

The worst-case scenario is going to court, dispensing with the husband’s signature and forcing the sale of the property, which Travers says takes time.

A simple house sale between a splitting couple that seems to agree on the terms may raise some red flags for lawyers. Tony Spagnuolo of Spagnuolo & Company Real Estate Lawyers in Coquitlam, B.C. will stand back if he sees a feuding couple selling the matrimonial home. If it’s clear that there are many unresolved issues that might manifest themselves in the house deal, he’ll suggest they each secure their own lawyer.

“If it’s a War of the Roses scenario, then we wouldn’t even act for both of the sides of the transaction; we would not act for both vendors,” says Spagnuolo. “If a couple is getting divorced and they’re really having it out, we would only act for the husband or wife; we would not act for both . . . just because it would be so easy for interests to collide later on down the road. It’s just easier if you just act for one party, rather than the two of them.”