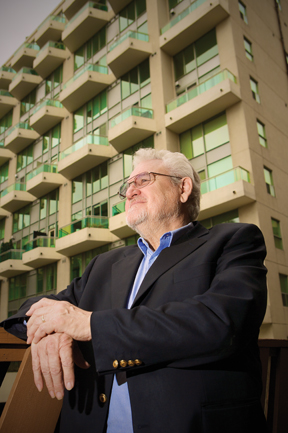

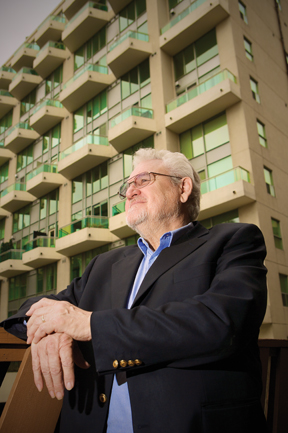

In the last 12 years, Roger Kerans has resolved disputes worth more than $1 billion, either through mediation or arbitration.

He’s also a leader in what’s called “fairness monitoring,” a process for overseeing procurement procedures for large public infrastructure projects. It has become big business in an age of alternative financing through public-private partnerships as governments seek to blunt potential criticism that they’ve favoured one contract bidder over another. In recent years, Kerans has reviewed more than $2-billion worth of contracts, including one tendered by the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority for the new Golden Ears Bridge.

He’s also a leader in what’s called “fairness monitoring,” a process for overseeing procurement procedures for large public infrastructure projects. It has become big business in an age of alternative financing through public-private partnerships as governments seek to blunt potential criticism that they’ve favoured one contract bidder over another. In recent years, Kerans has reviewed more than $2-billion worth of contracts, including one tendered by the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority for the new Golden Ears Bridge.

As a result, Kerans has established himself as one of Canada’s top professionals in alternative dispute resolution. He is in such high demand that he has been looking for ways to cut his workload. “I doubled my prices, and still the phone keeps ringing,” he said in Toronto recently for a fairness-monitoring assignment for the Ontario Realty Corp. “People still want him,” says Eva Christopher, a lawyer with Whitelaw Twining Law Corp. in Vancouver who has sought Kerans’ help as a mediator on about 10 cases.

What’s most remarkable about Kerans, however, is that he’s ostensibly retired. A former judge on the Alberta Court of Appeal, he left the bench in 1997 after a 27-year judicial career that saw him take a leading role in cases dealing with oil and gas law, contracts, and insurance matters. At the time, he had a list of things he was interested in doing, including computers and constitutional law. But so far, none of those plans has come to fruition. “What I do, none of them were on the list at the time,” he says. “My explanation is I don’t play golf, and that’s why I’m able to do all these things,” the 75-year-old adds. “My colleagues think I’m nuts.”

Since leaving the bench, he has at least followed his fellow retirees to Victoria, where he has done everything from writing columns on legal issues for The Globe and Mail to teaching at the University of Victoria. But he has made his biggest mark as a mediator, a role for which he has so far tallied almost 800 cases.

One of his more prominent negotiations was the recent landmark settlement of the class action case against Maple Leaf Foods over last year’s listeriosis outbreak. The tainted meat left 20 people dead and many more sick, a scenario that opened the prospect to years of litigation not only between the opposing sides but also among the many plaintiffs’ counsel involved in the case. But the parties surprised many observers in late January when they announced they had reached an agreement that will see the company pay as much as $27 million to victims or their next of kin.

Much credit has gone to Maple Leaf itself for acknowledging its role in the tragedy rather than denying responsibility, but lawyers involved praised Kerans as well for deftly prodding them towards a settlement despite significant disagreement amongst plaintiffs’ counsel along the way. It’s a case Kerans is particularly proud of. “To see them at the end of the day sign a settlement agreement is immensely satisfying, more satisfying than the judging business,” he says.

Kerans, in fact, boasts that his settlement failure rate is just three per cent. In Christopher’s case, she’s had an even better record before Kerans. “He has settled everything I’ve had him on,” she says.

Part of what distinguishes Kerans is that he’s not just a messenger who merely communicates settlement offers between the parties. “He’s a negotiator,” says Christopher, adding that Kerans’ experience as a judge is particularly valuable since he can speak with some authority about what the result would likely be if the parties were to take the case to court. As a result, his direct style of intervening when the parties reach an impasse can help with difficult clients with unrealistic expectations of what they’re going to get.

“It’s more the parties themselves who need to hear tough news once in a while,” she says. “It’s helpful to have that when you have client control issues.”

At the same time, Christopher says Kerans avoids the trap of other former judges who sometimes treat mediation cases as though they were in their previous role. “He doesn’t try to judge cases, which is sometimes the case with former judges who become mediators.”

For his part, Kerans says he can predict what the likely settlement outcome will be within 15 minutes of starting a mediation session. But his approach is first to let the parties get the emotional issues — the anger and frustration — off their chests before getting to the substance of a deal. “I wear them out — let them talk themselves out,” he says, noting that he gets aggressive in pushing for an agreement by about 5 p.m. when discussions look like they’re dragging on without progress.

At that point, he lets instinct guide what he should do next. If he feels it’s the lawyers who are hindering a deal, for example, he’ll ask them to leave the room so he can talk to the parties directly. In other cases, it might be simply that they don’t trust each other or that one party is asking for too much. Either way, Kerans says, the key is understanding why they’re not settling.

Besides a busy schedule crossing the country for mediations and arbitrations, Kerans is also active on the global scene as a member of the Canadian roster on the International Court of Arbitration in Paris. Much of that work takes him to the United States, where he tests his legal prowess by applying whichever jurisdiction’s laws the parties agree to use in the case. “I go one place and interpret the laws of another place,” he says.

But despite his globe-trotting, Kerans is beginning to pull back the throttle and at least take a crack at slowing down. He has put a stop, for example, to his monthly trips to Calgary for a week of mediations. Still, he makes it clear that he’s not completely retiring yet. “I say I’m not ready to start growing roses.”

Part of the reason he keeps going, of course, is his passion for the task of helping people settle their disputes. “Mediators are never wrong,” he says. “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t get them to drink. My ego is to get them to drink.”

He’s also a leader in what’s called “fairness monitoring,” a process for overseeing procurement procedures for large public infrastructure projects. It has become big business in an age of alternative financing through public-private partnerships as governments seek to blunt potential criticism that they’ve favoured one contract bidder over another. In recent years, Kerans has reviewed more than $2-billion worth of contracts, including one tendered by the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority for the new Golden Ears Bridge.

He’s also a leader in what’s called “fairness monitoring,” a process for overseeing procurement procedures for large public infrastructure projects. It has become big business in an age of alternative financing through public-private partnerships as governments seek to blunt potential criticism that they’ve favoured one contract bidder over another. In recent years, Kerans has reviewed more than $2-billion worth of contracts, including one tendered by the Greater Vancouver Transportation Authority for the new Golden Ears Bridge.As a result, Kerans has established himself as one of Canada’s top professionals in alternative dispute resolution. He is in such high demand that he has been looking for ways to cut his workload. “I doubled my prices, and still the phone keeps ringing,” he said in Toronto recently for a fairness-monitoring assignment for the Ontario Realty Corp. “People still want him,” says Eva Christopher, a lawyer with Whitelaw Twining Law Corp. in Vancouver who has sought Kerans’ help as a mediator on about 10 cases.

What’s most remarkable about Kerans, however, is that he’s ostensibly retired. A former judge on the Alberta Court of Appeal, he left the bench in 1997 after a 27-year judicial career that saw him take a leading role in cases dealing with oil and gas law, contracts, and insurance matters. At the time, he had a list of things he was interested in doing, including computers and constitutional law. But so far, none of those plans has come to fruition. “What I do, none of them were on the list at the time,” he says. “My explanation is I don’t play golf, and that’s why I’m able to do all these things,” the 75-year-old adds. “My colleagues think I’m nuts.”

Since leaving the bench, he has at least followed his fellow retirees to Victoria, where he has done everything from writing columns on legal issues for The Globe and Mail to teaching at the University of Victoria. But he has made his biggest mark as a mediator, a role for which he has so far tallied almost 800 cases.

One of his more prominent negotiations was the recent landmark settlement of the class action case against Maple Leaf Foods over last year’s listeriosis outbreak. The tainted meat left 20 people dead and many more sick, a scenario that opened the prospect to years of litigation not only between the opposing sides but also among the many plaintiffs’ counsel involved in the case. But the parties surprised many observers in late January when they announced they had reached an agreement that will see the company pay as much as $27 million to victims or their next of kin.

Much credit has gone to Maple Leaf itself for acknowledging its role in the tragedy rather than denying responsibility, but lawyers involved praised Kerans as well for deftly prodding them towards a settlement despite significant disagreement amongst plaintiffs’ counsel along the way. It’s a case Kerans is particularly proud of. “To see them at the end of the day sign a settlement agreement is immensely satisfying, more satisfying than the judging business,” he says.

Kerans, in fact, boasts that his settlement failure rate is just three per cent. In Christopher’s case, she’s had an even better record before Kerans. “He has settled everything I’ve had him on,” she says.

Part of what distinguishes Kerans is that he’s not just a messenger who merely communicates settlement offers between the parties. “He’s a negotiator,” says Christopher, adding that Kerans’ experience as a judge is particularly valuable since he can speak with some authority about what the result would likely be if the parties were to take the case to court. As a result, his direct style of intervening when the parties reach an impasse can help with difficult clients with unrealistic expectations of what they’re going to get.

“It’s more the parties themselves who need to hear tough news once in a while,” she says. “It’s helpful to have that when you have client control issues.”

At the same time, Christopher says Kerans avoids the trap of other former judges who sometimes treat mediation cases as though they were in their previous role. “He doesn’t try to judge cases, which is sometimes the case with former judges who become mediators.”

For his part, Kerans says he can predict what the likely settlement outcome will be within 15 minutes of starting a mediation session. But his approach is first to let the parties get the emotional issues — the anger and frustration — off their chests before getting to the substance of a deal. “I wear them out — let them talk themselves out,” he says, noting that he gets aggressive in pushing for an agreement by about 5 p.m. when discussions look like they’re dragging on without progress.

At that point, he lets instinct guide what he should do next. If he feels it’s the lawyers who are hindering a deal, for example, he’ll ask them to leave the room so he can talk to the parties directly. In other cases, it might be simply that they don’t trust each other or that one party is asking for too much. Either way, Kerans says, the key is understanding why they’re not settling.

Besides a busy schedule crossing the country for mediations and arbitrations, Kerans is also active on the global scene as a member of the Canadian roster on the International Court of Arbitration in Paris. Much of that work takes him to the United States, where he tests his legal prowess by applying whichever jurisdiction’s laws the parties agree to use in the case. “I go one place and interpret the laws of another place,” he says.

But despite his globe-trotting, Kerans is beginning to pull back the throttle and at least take a crack at slowing down. He has put a stop, for example, to his monthly trips to Calgary for a week of mediations. Still, he makes it clear that he’s not completely retiring yet. “I say I’m not ready to start growing roses.”

Part of the reason he keeps going, of course, is his passion for the task of helping people settle their disputes. “Mediators are never wrong,” he says. “You can lead a horse to water but you can’t get them to drink. My ego is to get them to drink.”