A year-over-year comparison of the number of applications for possible miscarriages of justice reveals a sharp decline in submissions, investigations, and decisions by the minister of Justice, with fewer cases returned to the courts for retrial or appeal.

That finding comes in light of a Justice Canada report issued late last week on the ministerial review process. Section 696.5 of the Criminal Code requires the minister of Justice to submit a report to Parliament with statistics on the number of applications submitted and investigated, and the number of decisions rendered.

That finding comes in light of a Justice Canada report issued late last week on the ministerial review process. Section 696.5 of the Criminal Code requires the minister of Justice to submit a report to Parliament with statistics on the number of applications submitted and investigated, and the number of decisions rendered.

The report also goes over the process by which convicts may seek ministerial review of their cases:

“Since 1892,” the report states, “the Minister of Justice has had the power, in one form or another, to review a criminal conviction under federal law to determine whether there may have been a miscarriage of justice. The current regime is set out in [ss.] 696.1-696.6 of the Criminal Code.

“. . . If the Minister is satisfied that those matters provide a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred, the Minister may grant the convicted person a remedy and return the case to the courts — either referring the case to a court of appeal to be heard as a new appeal or directing that a new trial be held.”

The report is a plain collection of numbers, with little to no context or analysis. However, a review of previous reports reveals a surprising trend.

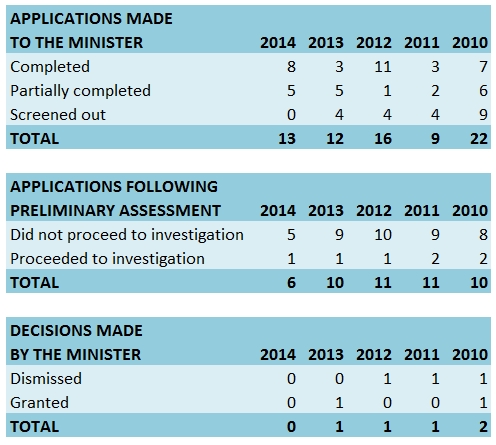

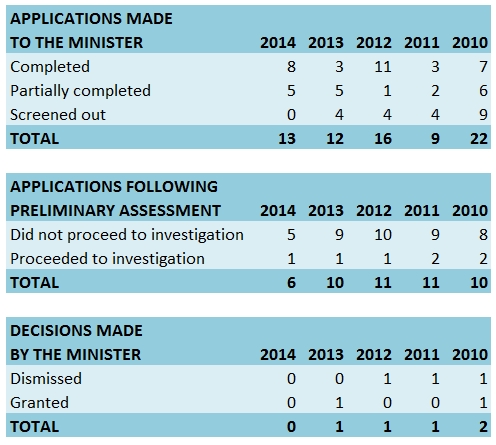

In the year to March 31, 2014, the number of applications for ministerial review reached 13, with no cases screened out. Four years earlier, the number of applications was 22, with nine cases screened out. (See accompanying table for a breakdown.)

While the report provides no explanation for the general trend, a sharp drop in submissions alongside a similarly sharp drop in screened-out applicants seems to suggest that weaker candidate cases are simply not being submitted for ministerial review.

The numbers also show fewer cases reaching the preliminary assessment stage after being screened out or abandoned by applicants (10 in 2010; 6 in 2014) and fewer cases reaching the investigation and decision stages (2 in 2010; none in 2014).

The miscarriage figures carry new weight in the wake of the Supreme Court of Canada ruling in R. v. Hart that casts doubt on “Mr. Big” convictions (where undercover agents convince suspects to confess to supposed partners in crime), and a call from the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted to review all such convictions.

AIDWYC could not be reached for this story, but when the ruling came out in August, AIDWYC director Russell Silverstein told Legal Feeds dozens of Mr. Big convictions were ripe for an audit.

“The important thing,” he said, “is to take it to the next step and to look at the cases of those who’ve been convicted based on this kind of scenario — who are outside the judicial system now with no further avenue of appeal — and get the federal government to audit those cases.”

If the government does conduct an audit on Mr. Big convictions, next year’s stats on ministerial review may show a spike in submissions.

That finding comes in light of a Justice Canada report issued late last week on the ministerial review process. Section 696.5 of the Criminal Code requires the minister of Justice to submit a report to Parliament with statistics on the number of applications submitted and investigated, and the number of decisions rendered.

That finding comes in light of a Justice Canada report issued late last week on the ministerial review process. Section 696.5 of the Criminal Code requires the minister of Justice to submit a report to Parliament with statistics on the number of applications submitted and investigated, and the number of decisions rendered.The report also goes over the process by which convicts may seek ministerial review of their cases:

“Since 1892,” the report states, “the Minister of Justice has had the power, in one form or another, to review a criminal conviction under federal law to determine whether there may have been a miscarriage of justice. The current regime is set out in [ss.] 696.1-696.6 of the Criminal Code.

“. . . If the Minister is satisfied that those matters provide a reasonable basis to conclude that a miscarriage of justice likely occurred, the Minister may grant the convicted person a remedy and return the case to the courts — either referring the case to a court of appeal to be heard as a new appeal or directing that a new trial be held.”

The report is a plain collection of numbers, with little to no context or analysis. However, a review of previous reports reveals a surprising trend.

In the year to March 31, 2014, the number of applications for ministerial review reached 13, with no cases screened out. Four years earlier, the number of applications was 22, with nine cases screened out. (See accompanying table for a breakdown.)

While the report provides no explanation for the general trend, a sharp drop in submissions alongside a similarly sharp drop in screened-out applicants seems to suggest that weaker candidate cases are simply not being submitted for ministerial review.

The numbers also show fewer cases reaching the preliminary assessment stage after being screened out or abandoned by applicants (10 in 2010; 6 in 2014) and fewer cases reaching the investigation and decision stages (2 in 2010; none in 2014).

The miscarriage figures carry new weight in the wake of the Supreme Court of Canada ruling in R. v. Hart that casts doubt on “Mr. Big” convictions (where undercover agents convince suspects to confess to supposed partners in crime), and a call from the Association in Defence of the Wrongly Convicted to review all such convictions.

AIDWYC could not be reached for this story, but when the ruling came out in August, AIDWYC director Russell Silverstein told Legal Feeds dozens of Mr. Big convictions were ripe for an audit.

“The important thing,” he said, “is to take it to the next step and to look at the cases of those who’ve been convicted based on this kind of scenario — who are outside the judicial system now with no further avenue of appeal — and get the federal government to audit those cases.”

If the government does conduct an audit on Mr. Big convictions, next year’s stats on ministerial review may show a spike in submissions.