A first-of-its-kind study published on Tuesday by the University of Toronto makes startling connections between the race and gender composition of law school graduates in Canada and where they land after their articles.

Entitled “Law and Beyond” (LAB), the report sheds light on who law students are today and what happens to them after graduation. Where do they end up? How much do they earn? Are they satisfied with their budding careers?

Some of the study’s more controversial findings include the fact that women and visible minorities are underrepresented across nearly all law firm categories (and overrepresented in public sector and business); black graduates are particularly underrepresented in this regard, with 42 percent working in the public sector (compared to 22 per cent for white grads). When it comes to income, female grads earn 93 per cent of what their male peers earn.

The LAB survey obtained responses from 1,099 recent graduates who were called to the bar in 2010. It’s modeled after a similar American study called “After the JD,” which has been tracking the class of 2000 in the United States for 13 years.

The LAB survey obtained responses from 1,099 recent graduates who were called to the bar in 2010. It’s modeled after a similar American study called “After the JD,” which has been tracking the class of 2000 in the United States for 13 years.

Sociologist Ronit Dinovitzer has been working on the American study for more than a decade, and she spearheaded the Canadian version. Though not a lawyer herself, Dinovitzer says she’s always been fascinated by the legal profession and how its composition impacts social justice principles and the economy.

“Lawyers are very important to the fabric of our society, to the rule of law, to access to justice. And so the question that brought me to this is, if you’ve got a profession that is so important, you’ve got to understand the internal dynamics of that profession . . . because if the legal profession can’t reflect democratic goals, then we’ve got to wonder and worry about it.”

Some key findings:

• 56 per cent of respondents are women; 22 per cent are visible minorities; 16 per cent are immigrants;

• 92 per cent have found work in legal practice since graduating;

• 63 per cent were hired back from their articling placement;

• 70 per cent work in private firms;

• 22 per cent work in the public sector;

• The average compensation of respondents is $78,000;

• 69 per cent have begun their careers at law firms; and

• women and visible minorities are more likely to work in the public sector.

The study categorizes graduates by gender (male, female) and racial groupings (white, black, Asian, South Asian, other) and categorizes employment positions by various characteristics (law firm size, law firm quality, business, government). Tracking these sorts of correlations is bound to create a stir, but Dinovitzer says the reaction has so far been positive.

The study categorizes graduates by gender (male, female) and racial groupings (white, black, Asian, South Asian, other) and categorizes employment positions by various characteristics (law firm size, law firm quality, business, government). Tracking these sorts of correlations is bound to create a stir, but Dinovitzer says the reaction has so far been positive.

“It’s been supportive. The law deans have written back, and they are happy to see this out there. I think there’s a real hunger for data, so I have not gotten any flak. I think for the most part, people want to see and know what’s going on.”

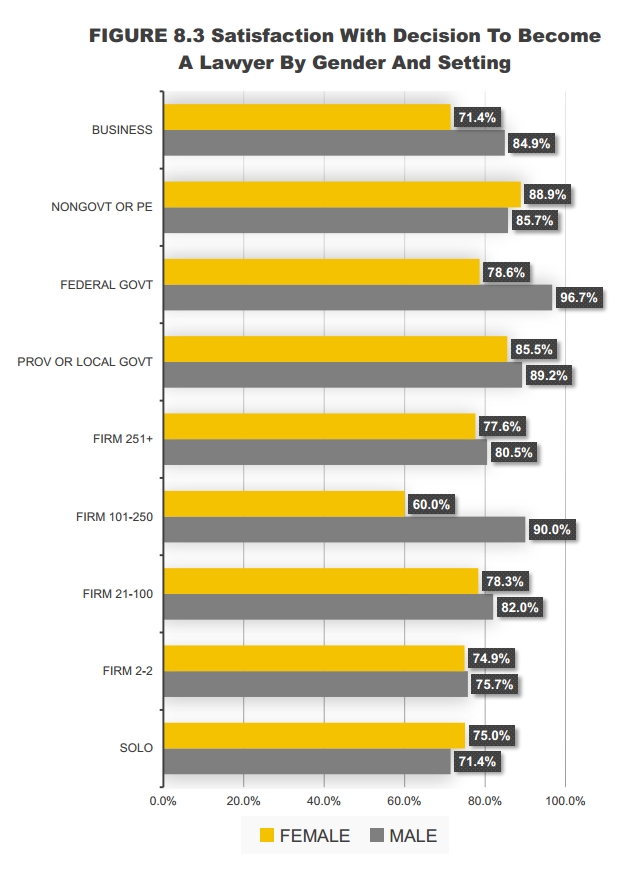

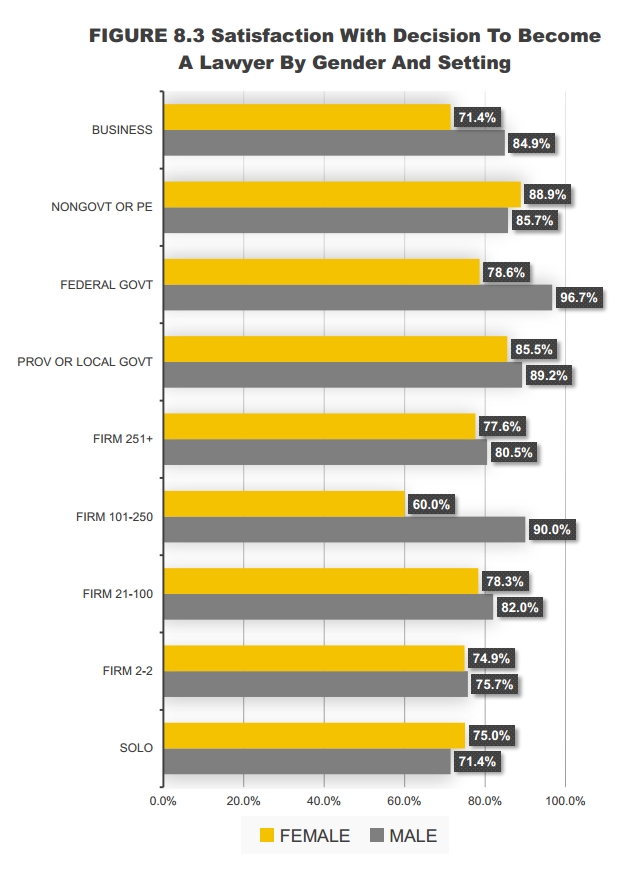

One surprising data point, for instance, shows that — contrary to all the professional doomsaying — law school grads are generally a satisfied bunch: 79 per cent report satisfaction with their decision to become lawyers, with the highest levels of satisfaction in provincial and federal government (at 87 per cent and 86 per cent respectively), and the lowest levels in solo practice (at 71 per cent).

Digging deeper into the numbers, however, the study finds a general malaise among female lawyers, who are underrepresented at larger firms and report lower levels of satisfaction than men across all professional settings except solo practice and non-governmental organizations.

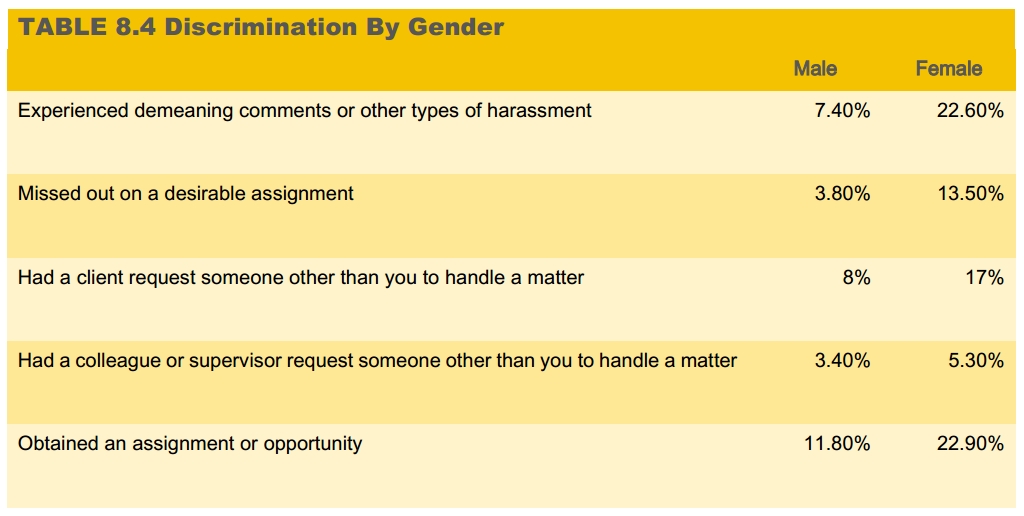

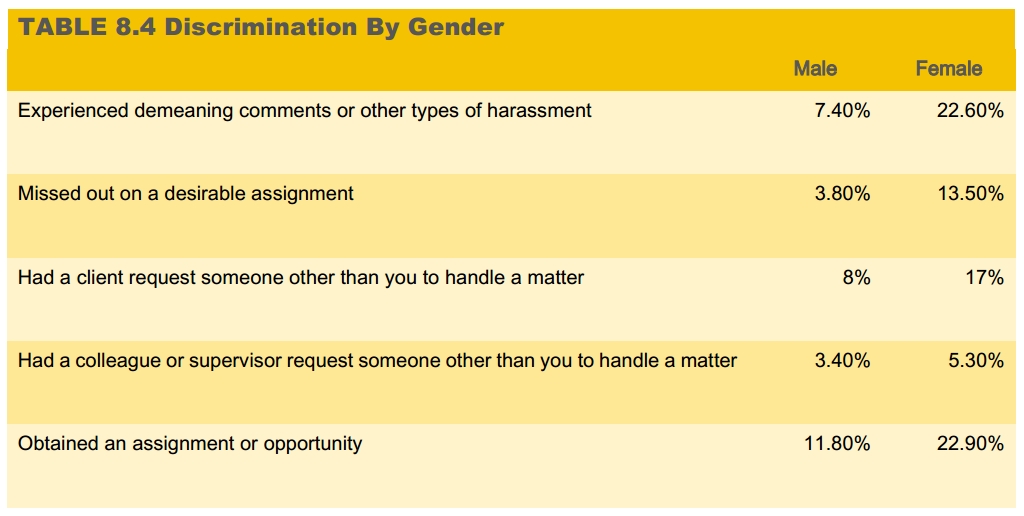

Dinovitzer is reluctant to make any assumptions about the underlying causes, but she notes a large percentage of recent female graduates (23 per cent) still report experiences with demeaning comments and harassment in the office.

“Some research shows that women or racial minorities feel that they don’t fit in when you put them in a position where they don’t feel supported. . . . It’s not just your current work situation, which of course is important, but it’s also your expectation for the future.”

While the study findings can be used to make sweeping generalizations about gender and racial groups that perpetuate stereotypes, Dinovitzer says she’s not worried about how the data will be misinterpreted. Willful ignorance will do nothing to address inequality issues in the legal profession, she says.

“This is just the first step,” she says. “I don’t just want to put it out there and leave it there. I want to try to figure out and zero in on some of these questions about the mechanisms that cause [these issues]. This is a long-term project, because I think if we don’t figure out what those mechanisms are, then you can actually effect meaningful change”

Entitled “Law and Beyond” (LAB), the report sheds light on who law students are today and what happens to them after graduation. Where do they end up? How much do they earn? Are they satisfied with their budding careers?

Some of the study’s more controversial findings include the fact that women and visible minorities are underrepresented across nearly all law firm categories (and overrepresented in public sector and business); black graduates are particularly underrepresented in this regard, with 42 percent working in the public sector (compared to 22 per cent for white grads). When it comes to income, female grads earn 93 per cent of what their male peers earn.

The LAB survey obtained responses from 1,099 recent graduates who were called to the bar in 2010. It’s modeled after a similar American study called “After the JD,” which has been tracking the class of 2000 in the United States for 13 years.

The LAB survey obtained responses from 1,099 recent graduates who were called to the bar in 2010. It’s modeled after a similar American study called “After the JD,” which has been tracking the class of 2000 in the United States for 13 years.Sociologist Ronit Dinovitzer has been working on the American study for more than a decade, and she spearheaded the Canadian version. Though not a lawyer herself, Dinovitzer says she’s always been fascinated by the legal profession and how its composition impacts social justice principles and the economy.

“Lawyers are very important to the fabric of our society, to the rule of law, to access to justice. And so the question that brought me to this is, if you’ve got a profession that is so important, you’ve got to understand the internal dynamics of that profession . . . because if the legal profession can’t reflect democratic goals, then we’ve got to wonder and worry about it.”

Some key findings:

• 56 per cent of respondents are women; 22 per cent are visible minorities; 16 per cent are immigrants;

• 92 per cent have found work in legal practice since graduating;

• 63 per cent were hired back from their articling placement;

• 70 per cent work in private firms;

• 22 per cent work in the public sector;

• The average compensation of respondents is $78,000;

• 69 per cent have begun their careers at law firms; and

• women and visible minorities are more likely to work in the public sector.

The study categorizes graduates by gender (male, female) and racial groupings (white, black, Asian, South Asian, other) and categorizes employment positions by various characteristics (law firm size, law firm quality, business, government). Tracking these sorts of correlations is bound to create a stir, but Dinovitzer says the reaction has so far been positive.

The study categorizes graduates by gender (male, female) and racial groupings (white, black, Asian, South Asian, other) and categorizes employment positions by various characteristics (law firm size, law firm quality, business, government). Tracking these sorts of correlations is bound to create a stir, but Dinovitzer says the reaction has so far been positive.“It’s been supportive. The law deans have written back, and they are happy to see this out there. I think there’s a real hunger for data, so I have not gotten any flak. I think for the most part, people want to see and know what’s going on.”

One surprising data point, for instance, shows that — contrary to all the professional doomsaying — law school grads are generally a satisfied bunch: 79 per cent report satisfaction with their decision to become lawyers, with the highest levels of satisfaction in provincial and federal government (at 87 per cent and 86 per cent respectively), and the lowest levels in solo practice (at 71 per cent).

Digging deeper into the numbers, however, the study finds a general malaise among female lawyers, who are underrepresented at larger firms and report lower levels of satisfaction than men across all professional settings except solo practice and non-governmental organizations.

Dinovitzer is reluctant to make any assumptions about the underlying causes, but she notes a large percentage of recent female graduates (23 per cent) still report experiences with demeaning comments and harassment in the office.

“Some research shows that women or racial minorities feel that they don’t fit in when you put them in a position where they don’t feel supported. . . . It’s not just your current work situation, which of course is important, but it’s also your expectation for the future.”

While the study findings can be used to make sweeping generalizations about gender and racial groups that perpetuate stereotypes, Dinovitzer says she’s not worried about how the data will be misinterpreted. Willful ignorance will do nothing to address inequality issues in the legal profession, she says.

“This is just the first step,” she says. “I don’t just want to put it out there and leave it there. I want to try to figure out and zero in on some of these questions about the mechanisms that cause [these issues]. This is a long-term project, because I think if we don’t figure out what those mechanisms are, then you can actually effect meaningful change”