Law firms are being hit with a flood of legal work as Asian investment continues to grow

The hiring joke in the Vancouver legal community is that every firm wants a “unicorn” — a First Nations lawyer capable of speaking Mandarin.

It exemplifies the two growth areas in the Vancouver legal market, but most agree the swell of Asian dollars is leading, as Vancouver remains a hot spot for yet another wave of Asian immigrant investors. The new 15-per-cent property transfer tax imposed by the B.C. Liberal government on foreign homebuyers is expected to kick out the speculator, but it won’t deter the true investor who sees Metro Vancouver as a safe haven for cash.

“It is almost a tsunami,” says Edmond Luke, a partner at Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP, who heads the Asia Pacific Group, when he talks about the latest influx of immigrants and cash.

The tax may break the wave at its edges but not its strong base as the trend is entrenched, fuelled by the underpinnings of a large Asian business community in Metro Vancouver, and Vancouver International Airport, which boasts all five major Asian carriers and more Chinese carriers than any other airport in the Americas. “The entire platform [for Asian investment] has been built over the past 30 years,” Luke says of the time China’s central government embraced private entrepreneurship. It is not going away.

“This latest wave started in 2000 and we are at 2016; each year it just seems to be getting bigger,” says Luke, as immigrant investors or foreign Asian companies bring in capital to partner with Canadian companies, invest in real estate developments or acquire assets. Previous investment waves have not lasted 16 years, he says, another reason he doubts the transfer tax will deter serious investors.

“They may have to tweak it,” he says, as the Liberals realize that new tax catches legitimate investors in the same net as speculators.

The inbound Asian investors seeking out legal firms are a far cry from earlier waves. They are entrepreneurial, worldly, as they often navigate on a global basis, and better educated. They are more sophisticated, says Luke. The early wave cloistered around Vancouver’s Chinatown, now more of a tourist haunt, while later waves settled in nearby Richmond, which sounds like “rich man” but translates into “gateway to fortune.”

This new wave is settling throughout Metro Vancouver, not intimidated by the seven-digit price stickers on homes in the Lower Mainland. The South China Morning Post reported that, since 2002, more than 60,000 millionaire migrants and family members have arrived in Vancouver.

“There is no doubt that they are savvy players in the real estate market,” says managing partner Keith Mitchell of Farris Vaughan Wills & Murphy LLP. “They see real estate as an important component of an investment portfolio and their long-term thinking. They are inter-generational thinkers. They value what we have here — a clean environment, a good health-care system and a good education system.” He says the influx of new arrivals are coming to Farris for a range of services, ranging from estate planning to legal advice on taxation on investments and facilitating new investments made here. Mitchell also sees the trend as a rising one and more Asian-B.C. joint-venture business happening on the horizon as the Asian countries are rimmed around B.C. “We see the phenomenon continuing,” he says.

Victor Tsao, managing partner in the Vancouver office of DS Avocats, agrees that the new tax, which was applied as of Aug. 2, will have a moderating impact on the speculator. He worries, though, that others caught in the net will serve as a punitive measure to legitimate immigrants who are coming to live and invest and are in the immigration process. “They usually like to buy something before arriving,” he says. Investors will still come to the Greater Vancouver area, he believes, but they will now suffer a burden.

Victor Tsao, managing partner in the Vancouver office of DS Avocats, agrees that the new tax, which was applied as of Aug. 2, will have a moderating impact on the speculator. He worries, though, that others caught in the net will serve as a punitive measure to legitimate immigrants who are coming to live and invest and are in the immigration process. “They usually like to buy something before arriving,” he says. Investors will still come to the Greater Vancouver area, he believes, but they will now suffer a burden.

The latest influx of Asian dollars he has seen has come from commuting fathers, dubbed “astronauts,” from Hong Kong, Taiwan and China, who brought their wife and children to Canada attracted by Canada’s excellent education facilities, stable politics and a clean environment. They are no longer commuting. “That has ended dramatically,” says Tsao. The children have now graduated university, settled in Canada and have families. Pulled in by the magnetism of family and grandchildren, the travelling dads are now winding down their foreign businesses.

They are moving cash to Vancouver as they seek investment opportunities ranging from hotels to property development.

Tsao says DS Avocat’s strong presence in the Asian market (with three offices in China) drew him to boost the firm’s presence in the Vancouver market. “It was important to me because a large part of my practice is inbound Chinese investors,” he says, including returning fathers to state-owned and private companies out of China.

State-owned enterprises dominated until China’s central government policy changed in the late 1970s and private entreprises and non-government entities emerged. While there are still SOEs run by all levels of Chinese government, Tsao says SOEs have changed. There is less of a government grip on management, allowing the professionals to direct the company.

The SOEs have also sharpened up. In late 2008, the fast-paced Chinese economy was insatiable for resource-based acquisitions to fuel a raging growth and billions of dollars were directed internationally, including Canada, to locking down resources. “A lot were outright failures,” says Tsao as investments were made when commodity prices were high and economies subsequently tanked. The Chinese economy also cooled and so did SOE investment. The non-SOEs emerged in the next wave looking at technology and manufacturing opportunities with more success.

“We now have another wave of the SOEs — they are back,” says Tsao, but with a shrewder view of the marketplace and a more discriminating buying taste. “They are on their next round of investments and acquisitions,” he says, moving into industries ranging from technology to pharmaceuticals. “They have become aware that the Canadian market is more than just oil and minerals.”

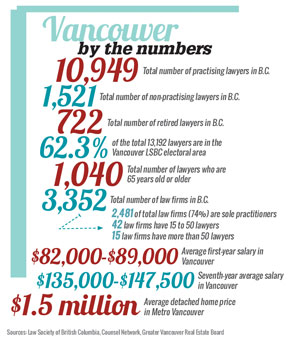

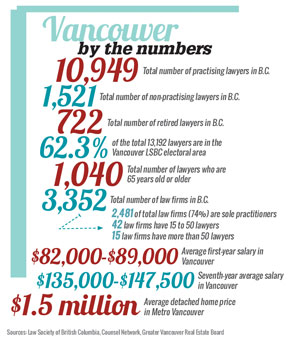

The wave is creating more business. Recruiter and lawyer David Namkung, partner in The Counsel Network, sees an uptick in demand from law firms looking for lawyers with Chinese language skills. “We noticed the trend this last year,” he says. Mandarin (China and Taiwan’s official language, as well as one of four spoken in Singapore) tops the list. “It is one of the dominant skills for those who want to court business in China, and also Mandarin is paramount for those acting as family lawyers or on mergers and acquisitions. And in real estate, of course,” says Namkung, who is the newly elected president of the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers. FACL BC’s membership nearly tripled in the past year reaching 228 from 83 last year and is part of a 1,500-member-strong national body.

The jury is still out as to whether Asian languages are a must-have skill. Fasken’s Luke doesn’t see it as a necessity for lawyers working in his 60-to-70-person Asia Pacific Group where 30 to 40 lawyers do the core of the work in China. Of those, half are of Chinese descent and only 10 speak Chinese. “That hasn’t stopped us or slowed us down in the opportunities that we have been able to take on,” he says.

Jim M.J. Alam of Koffman Kalef LLP practises in the area of real estate developments and banking and he’s seeing more and more Asian investor groups wanting to joint-venture with local developers. The firm helps with the land acquisition, assembly and development of the project, albeit residential or commercial. He says most Asian groups feel comfortable relying upon the Canadian developer to work with the local authorities in the marketplace. “They value that the local developer brings the ability to navigate the various processes with the municipality and that they have the connections with the building trades and the marketplace,” says Alam.

The firm relies upon translators or the developer’s in-house staff to communicate with the Asian investor. “There have been discussions around our partners’ table about whether we should be adding language skills,” he says, believing that they are becoming increasingly important. The firm may sit in on early negotiations and he sees the benefit in having the ability to monitor the flow of information the translator is providing.

McMillan’s Steve Wortley, in charge of the firm’s Hong Kong office and co-chairman of the firm’s China Investment Group, thinks there will only be a deepening of business ventures between China and Vancouver.

McMillan opted into the Chinese market early, focusing on three thrusts: investing dollars from China into Canada, bringing Canadian dollars into Chinese efforts, and helping Chinese companies gain exposure to the Canadian stock exchanges. It started in the 1990s with Wortley bringing Chinese companies to the Toronto Stock Exchange and firms establishing in Vancouver. He’s seen the Asian flow of dollars deepen in joint-ventures, new businesses and acquisitions. (Even the Agricultural Bank of China has headquarters in Vancouver.) He credits much of the growth to the 2012 forged tax agreement between Hong Kong and Canada.

“The real driver has been the Hong Kong Double Tax Agreement,” Wortley says, as it allows investment dividends returned to Hong Kong to be taxed as low as five per cent from a high of 25 per cent tax.

Wortley doesn’t see Chinese investment ebbing; the growing wealth in a burgeoning middle class and government-supported investment banks are both looking abroad for new investment opportunities.

But changes have occurred. In the past, Chinese investors have been reluctant to seek third-party advice on deals until they were well along. They are now more open to let investment banks, accountants and lawyers help evaluate opportunities, he says.

The other trend is that investors are looking at “broader opportunities” that are “more meaningful,” he says, referring to the Harbour Air Seaplanes deal with which McMillan was involved.

The Zongshen’s Tianchen General Aviation Co. picked up 49 per cent of the coastal seaplane company, including 25 per cent of its voting shares, in 2015. Part of the agreement sees Harbour Air’s pilots training Chinese seaplane pilots so that seaplane charter service can be offered along China’s major rivers. While the B.C. company benefited from the investment by allowing it to grow, the Chinese company took expertise home to a burgeoning new market as Chinese private air space opened.

“The best transactions are those that bring components [new businesses] and capital into Canada and allow Canadian management and know-how to be brought out to different parts of the world,” says Wortley.

The hiring joke in the Vancouver legal community is that every firm wants a “unicorn” — a First Nations lawyer capable of speaking Mandarin.

It exemplifies the two growth areas in the Vancouver legal market, but most agree the swell of Asian dollars is leading, as Vancouver remains a hot spot for yet another wave of Asian immigrant investors. The new 15-per-cent property transfer tax imposed by the B.C. Liberal government on foreign homebuyers is expected to kick out the speculator, but it won’t deter the true investor who sees Metro Vancouver as a safe haven for cash.

“It is almost a tsunami,” says Edmond Luke, a partner at Fasken Martineau DuMoulin LLP, who heads the Asia Pacific Group, when he talks about the latest influx of immigrants and cash.

The tax may break the wave at its edges but not its strong base as the trend is entrenched, fuelled by the underpinnings of a large Asian business community in Metro Vancouver, and Vancouver International Airport, which boasts all five major Asian carriers and more Chinese carriers than any other airport in the Americas. “The entire platform [for Asian investment] has been built over the past 30 years,” Luke says of the time China’s central government embraced private entrepreneurship. It is not going away.

“This latest wave started in 2000 and we are at 2016; each year it just seems to be getting bigger,” says Luke, as immigrant investors or foreign Asian companies bring in capital to partner with Canadian companies, invest in real estate developments or acquire assets. Previous investment waves have not lasted 16 years, he says, another reason he doubts the transfer tax will deter serious investors.

“They may have to tweak it,” he says, as the Liberals realize that new tax catches legitimate investors in the same net as speculators.

The inbound Asian investors seeking out legal firms are a far cry from earlier waves. They are entrepreneurial, worldly, as they often navigate on a global basis, and better educated. They are more sophisticated, says Luke. The early wave cloistered around Vancouver’s Chinatown, now more of a tourist haunt, while later waves settled in nearby Richmond, which sounds like “rich man” but translates into “gateway to fortune.”

This new wave is settling throughout Metro Vancouver, not intimidated by the seven-digit price stickers on homes in the Lower Mainland. The South China Morning Post reported that, since 2002, more than 60,000 millionaire migrants and family members have arrived in Vancouver.

“There is no doubt that they are savvy players in the real estate market,” says managing partner Keith Mitchell of Farris Vaughan Wills & Murphy LLP. “They see real estate as an important component of an investment portfolio and their long-term thinking. They are inter-generational thinkers. They value what we have here — a clean environment, a good health-care system and a good education system.” He says the influx of new arrivals are coming to Farris for a range of services, ranging from estate planning to legal advice on taxation on investments and facilitating new investments made here. Mitchell also sees the trend as a rising one and more Asian-B.C. joint-venture business happening on the horizon as the Asian countries are rimmed around B.C. “We see the phenomenon continuing,” he says.

Victor Tsao, managing partner in the Vancouver office of DS Avocats, agrees that the new tax, which was applied as of Aug. 2, will have a moderating impact on the speculator. He worries, though, that others caught in the net will serve as a punitive measure to legitimate immigrants who are coming to live and invest and are in the immigration process. “They usually like to buy something before arriving,” he says. Investors will still come to the Greater Vancouver area, he believes, but they will now suffer a burden.

Victor Tsao, managing partner in the Vancouver office of DS Avocats, agrees that the new tax, which was applied as of Aug. 2, will have a moderating impact on the speculator. He worries, though, that others caught in the net will serve as a punitive measure to legitimate immigrants who are coming to live and invest and are in the immigration process. “They usually like to buy something before arriving,” he says. Investors will still come to the Greater Vancouver area, he believes, but they will now suffer a burden. The latest influx of Asian dollars he has seen has come from commuting fathers, dubbed “astronauts,” from Hong Kong, Taiwan and China, who brought their wife and children to Canada attracted by Canada’s excellent education facilities, stable politics and a clean environment. They are no longer commuting. “That has ended dramatically,” says Tsao. The children have now graduated university, settled in Canada and have families. Pulled in by the magnetism of family and grandchildren, the travelling dads are now winding down their foreign businesses.

They are moving cash to Vancouver as they seek investment opportunities ranging from hotels to property development.

Tsao says DS Avocat’s strong presence in the Asian market (with three offices in China) drew him to boost the firm’s presence in the Vancouver market. “It was important to me because a large part of my practice is inbound Chinese investors,” he says, including returning fathers to state-owned and private companies out of China.

State-owned enterprises dominated until China’s central government policy changed in the late 1970s and private entreprises and non-government entities emerged. While there are still SOEs run by all levels of Chinese government, Tsao says SOEs have changed. There is less of a government grip on management, allowing the professionals to direct the company.

The SOEs have also sharpened up. In late 2008, the fast-paced Chinese economy was insatiable for resource-based acquisitions to fuel a raging growth and billions of dollars were directed internationally, including Canada, to locking down resources. “A lot were outright failures,” says Tsao as investments were made when commodity prices were high and economies subsequently tanked. The Chinese economy also cooled and so did SOE investment. The non-SOEs emerged in the next wave looking at technology and manufacturing opportunities with more success.

“We now have another wave of the SOEs — they are back,” says Tsao, but with a shrewder view of the marketplace and a more discriminating buying taste. “They are on their next round of investments and acquisitions,” he says, moving into industries ranging from technology to pharmaceuticals. “They have become aware that the Canadian market is more than just oil and minerals.”

The wave is creating more business. Recruiter and lawyer David Namkung, partner in The Counsel Network, sees an uptick in demand from law firms looking for lawyers with Chinese language skills. “We noticed the trend this last year,” he says. Mandarin (China and Taiwan’s official language, as well as one of four spoken in Singapore) tops the list. “It is one of the dominant skills for those who want to court business in China, and also Mandarin is paramount for those acting as family lawyers or on mergers and acquisitions. And in real estate, of course,” says Namkung, who is the newly elected president of the Federation of Asian Canadian Lawyers. FACL BC’s membership nearly tripled in the past year reaching 228 from 83 last year and is part of a 1,500-member-strong national body.

The jury is still out as to whether Asian languages are a must-have skill. Fasken’s Luke doesn’t see it as a necessity for lawyers working in his 60-to-70-person Asia Pacific Group where 30 to 40 lawyers do the core of the work in China. Of those, half are of Chinese descent and only 10 speak Chinese. “That hasn’t stopped us or slowed us down in the opportunities that we have been able to take on,” he says.

Jim M.J. Alam of Koffman Kalef LLP practises in the area of real estate developments and banking and he’s seeing more and more Asian investor groups wanting to joint-venture with local developers. The firm helps with the land acquisition, assembly and development of the project, albeit residential or commercial. He says most Asian groups feel comfortable relying upon the Canadian developer to work with the local authorities in the marketplace. “They value that the local developer brings the ability to navigate the various processes with the municipality and that they have the connections with the building trades and the marketplace,” says Alam.

The firm relies upon translators or the developer’s in-house staff to communicate with the Asian investor. “There have been discussions around our partners’ table about whether we should be adding language skills,” he says, believing that they are becoming increasingly important. The firm may sit in on early negotiations and he sees the benefit in having the ability to monitor the flow of information the translator is providing.

McMillan’s Steve Wortley, in charge of the firm’s Hong Kong office and co-chairman of the firm’s China Investment Group, thinks there will only be a deepening of business ventures between China and Vancouver.

McMillan opted into the Chinese market early, focusing on three thrusts: investing dollars from China into Canada, bringing Canadian dollars into Chinese efforts, and helping Chinese companies gain exposure to the Canadian stock exchanges. It started in the 1990s with Wortley bringing Chinese companies to the Toronto Stock Exchange and firms establishing in Vancouver. He’s seen the Asian flow of dollars deepen in joint-ventures, new businesses and acquisitions. (Even the Agricultural Bank of China has headquarters in Vancouver.) He credits much of the growth to the 2012 forged tax agreement between Hong Kong and Canada.

“The real driver has been the Hong Kong Double Tax Agreement,” Wortley says, as it allows investment dividends returned to Hong Kong to be taxed as low as five per cent from a high of 25 per cent tax.

Wortley doesn’t see Chinese investment ebbing; the growing wealth in a burgeoning middle class and government-supported investment banks are both looking abroad for new investment opportunities.

But changes have occurred. In the past, Chinese investors have been reluctant to seek third-party advice on deals until they were well along. They are now more open to let investment banks, accountants and lawyers help evaluate opportunities, he says.

The other trend is that investors are looking at “broader opportunities” that are “more meaningful,” he says, referring to the Harbour Air Seaplanes deal with which McMillan was involved.

The Zongshen’s Tianchen General Aviation Co. picked up 49 per cent of the coastal seaplane company, including 25 per cent of its voting shares, in 2015. Part of the agreement sees Harbour Air’s pilots training Chinese seaplane pilots so that seaplane charter service can be offered along China’s major rivers. While the B.C. company benefited from the investment by allowing it to grow, the Chinese company took expertise home to a burgeoning new market as Chinese private air space opened.

“The best transactions are those that bring components [new businesses] and capital into Canada and allow Canadian management and know-how to be brought out to different parts of the world,” says Wortley.