A British Columbia first nation announced Wednesday that it will launch a class-action lawsuit against the B.C. and federal government for a second time to end commercial open net-pen salmon farming in the Broughton Archipelago.

The Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation (KAFN) said it will renew its legal action to protect wild salmon in its territory from diseases allegedly spread by nearby salmon farms after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled aboriginal collectives should not be allowed to join together in a class action in May.

The Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation (KAFN) said it will renew its legal action to protect wild salmon in its territory from diseases allegedly spread by nearby salmon farms after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled aboriginal collectives should not be allowed to join together in a class action in May.

Bob Chamberlin, KAFN chief and representative plaintiff in the action, chided both the Canadian and B.C. governments Aug. 8, saying their continued support of the aquaculture industry ignores its environmental impact on wild salmon populations and has forced the First Nation to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

“The appeal of our certification win by both the Canadian and B.C. governments, and supported by the aquaculture industry, hinged on technicalities and missed the importance of government’s obligation to regulate the open net salmon farming industry in a way that protects wild salmon,” said Chief Chamberlin. “This decision cannot remain unchallenged.”

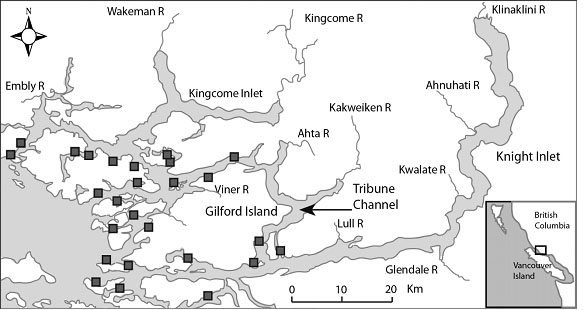

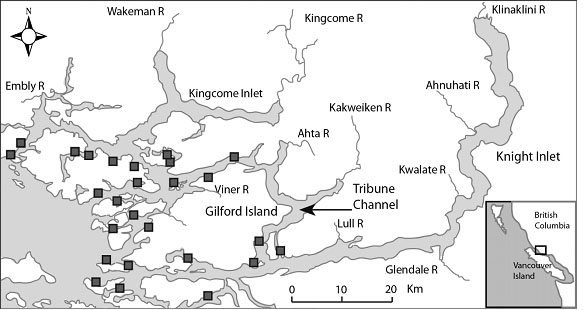

KAFN first sought certification as a class against the B.C. government in February 2009. In KAFN’s statement of claim filed in the B.C. Supreme Court, it argued the B.C. government should be required to address the decline in wild salmon in the First Nation’s traditional territory, sought damages, and sought a declaration that the first nation has fishing rights in the Broughton Archipelago, among other remedies.

B.C. Supreme Court Justice Harry Slade certified the class action in December 2010. The certification marked the first class-action lawsuit advanced by a First Nation in Canada to protect aboriginal fishing rights.

Slade ruled that First Nations could be classified as a band and therefore could meet the test for class certification under the Indian Act as members of a shared culture with similar interests.

But the B.C. and Canadian governments later appealed the decision, with Justice Nicole Garson overturning Slade’s ruling in May 2012. Garson determined the First Nation could not clearly identify its class members, and therefore could not win certification as a class due to a lack of legal capacity and known objective criteria.

“Because class proceeding legislation is procedural, and does not create substantive rights, a proposed class action must identify class members who individually have legal capacity to sue and assert a cause of action,” Garson wrote in her May 3 decision Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation v. Canada (Attorney General).

Garson continued: “Before certification, that action was a representative action brought by a person who does have legal capacity. However, the certification of Chief Chamberlin’s representative action on behalf of ‘Aboriginal collectives’ fails to specify objective criteria by which a collective could, without an ethnographic analysis and court determination, identify its membership in the class. This analysis would be part of the infringement analysis which the certification order leaves to a later determination of the individual issues. Moreover, the term ‘Aboriginal collective,’ does not, without more, identify a group that has legal capacity.”

While much attention has been focused on the environmental impact of open net-pen commercial salmon farming on aboriginal people, a successful application for leave to appeal to the SCC would be particularly important as it would consider whether aboriginal collectives can be certified as a class.

Currently, most claims of aboriginal rights and titles brought to the courts are through a representative action where one member of the group becomes the representative plaintiff for the remainder of the group, making it easier to represent all the members of an entity.

However, one of the questions for the top court, pending a successful application for leave to appeal, may become whether the tried-and-true method of representative actions unnecessarily limits or hinders certification as a class action for aboriginal collectives.

The Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation (KAFN) said it will renew its legal action to protect wild salmon in its territory from diseases allegedly spread by nearby salmon farms after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled aboriginal collectives should not be allowed to join together in a class action in May.

The Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation (KAFN) said it will renew its legal action to protect wild salmon in its territory from diseases allegedly spread by nearby salmon farms after the B.C. Court of Appeal ruled aboriginal collectives should not be allowed to join together in a class action in May.Bob Chamberlin, KAFN chief and representative plaintiff in the action, chided both the Canadian and B.C. governments Aug. 8, saying their continued support of the aquaculture industry ignores its environmental impact on wild salmon populations and has forced the First Nation to appeal to the Supreme Court of Canada.

“The appeal of our certification win by both the Canadian and B.C. governments, and supported by the aquaculture industry, hinged on technicalities and missed the importance of government’s obligation to regulate the open net salmon farming industry in a way that protects wild salmon,” said Chief Chamberlin. “This decision cannot remain unchallenged.”

KAFN first sought certification as a class against the B.C. government in February 2009. In KAFN’s statement of claim filed in the B.C. Supreme Court, it argued the B.C. government should be required to address the decline in wild salmon in the First Nation’s traditional territory, sought damages, and sought a declaration that the first nation has fishing rights in the Broughton Archipelago, among other remedies.

B.C. Supreme Court Justice Harry Slade certified the class action in December 2010. The certification marked the first class-action lawsuit advanced by a First Nation in Canada to protect aboriginal fishing rights.

Slade ruled that First Nations could be classified as a band and therefore could meet the test for class certification under the Indian Act as members of a shared culture with similar interests.

But the B.C. and Canadian governments later appealed the decision, with Justice Nicole Garson overturning Slade’s ruling in May 2012. Garson determined the First Nation could not clearly identify its class members, and therefore could not win certification as a class due to a lack of legal capacity and known objective criteria.

“Because class proceeding legislation is procedural, and does not create substantive rights, a proposed class action must identify class members who individually have legal capacity to sue and assert a cause of action,” Garson wrote in her May 3 decision Kwicksutaineuk/Ah-Kwa-Mish First Nation v. Canada (Attorney General).

Garson continued: “Before certification, that action was a representative action brought by a person who does have legal capacity. However, the certification of Chief Chamberlin’s representative action on behalf of ‘Aboriginal collectives’ fails to specify objective criteria by which a collective could, without an ethnographic analysis and court determination, identify its membership in the class. This analysis would be part of the infringement analysis which the certification order leaves to a later determination of the individual issues. Moreover, the term ‘Aboriginal collective,’ does not, without more, identify a group that has legal capacity.”

While much attention has been focused on the environmental impact of open net-pen commercial salmon farming on aboriginal people, a successful application for leave to appeal to the SCC would be particularly important as it would consider whether aboriginal collectives can be certified as a class.

Currently, most claims of aboriginal rights and titles brought to the courts are through a representative action where one member of the group becomes the representative plaintiff for the remainder of the group, making it easier to represent all the members of an entity.

However, one of the questions for the top court, pending a successful application for leave to appeal, may become whether the tried-and-true method of representative actions unnecessarily limits or hinders certification as a class action for aboriginal collectives.