Legal professionals can now brush up on international law while supporting a good cause thanks to a new program from the Canadian Centre for International Justice.

Taught by members of the legal community, the Philippe Kirsch Institute will offer legal professionals courses to advance their knowledge of international justice. All proceeds of the program will go directly towards the organization’s charity, which helps victims of torture and war crimes seek justice.

Taught by members of the legal community, the Philippe Kirsch Institute will offer legal professionals courses to advance their knowledge of international justice. All proceeds of the program will go directly towards the organization’s charity, which helps victims of torture and war crimes seek justice.

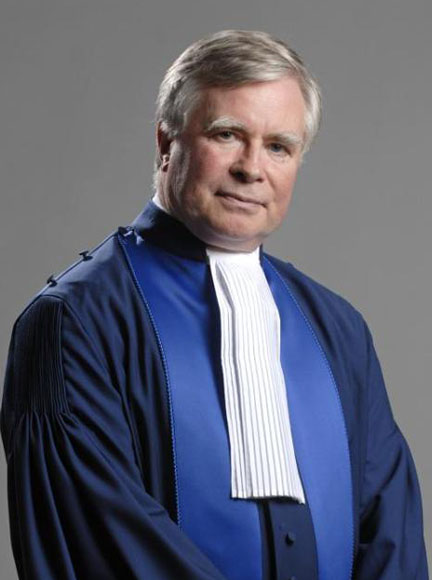

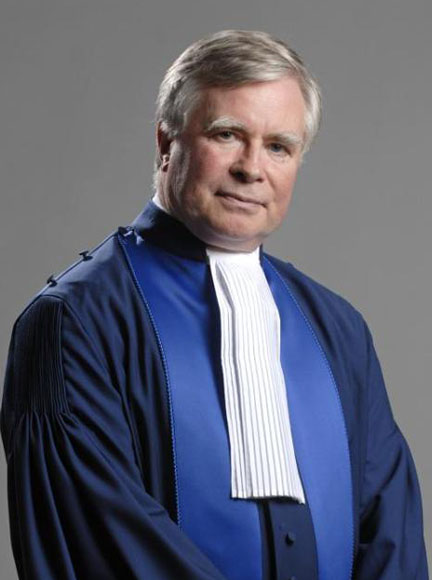

Named after internationally recognized Quebec jurist Philippe Kirsch, the institute is scheduled to be up-and-running within the year, and enable legal professionals to apply the CCIJ’s knowledge of international justice to other areas of the Canadian legal system.

According to Jayne Stoyles, executive director of the CCIJ, the institute was designed to serve a “dual purpose” of providing “legal training to the legal community” as well as utilizing the proceeds raised “to fund the CCIJ’s charitable legal work.”

Often referred to a “social enterprise,” this relatively new business model has been called “innovative” by professionals from the CCIJ’s ability to draw a profit for their social mission.

“It is a really challenging time for charities in Canada, and we’re just finding that our services are overstretching our resources and we don’t want to have to turn anyone away, so we decided to get really creative,” says Stoyles, who adds the idea to create the institute came after the CCIJ began to offer courses on international justice in 2000. “Rather than going as one more charity asking for donations, we thought that we could actually offer our expertise and make some of our own revenue.”

Kirsch is thrilled to be part of the initiative.

“CCIJ has an important mandate to fulfill, serving some of the hundreds of thousands of survivors of atrocities currently in Canada, while contributing to the global effort to send a message to would-be torturers and war criminals that they will face justice,” he says. “The business plan for the training institute has been very carefully prepared, and it is my strong expectation that the training will be highly sought after. This will provide a great service to the legal community in Canada, at the same time that it assists CCIJ in achieving its goals over the long term.”

Stoyles predicts there will be about 30 instructors for the planned 10 courses offered to prospective participants, which will have similar rates to other professional development courses in the market.

Courses are planned to teach participants how international law applies to Canadian legislation, and will include subjects involving civil litigation, immigration refugee law, criminal defence and criminal prosecution. Other planned areas of training include: how to provide services to torture survivors, and how to bring a case before an international body.

Taught by lawyers and judges involved in the CCIJ, including Kirsch, Stoyles promises the courses will provide “very high quality training” with the CCIJ having a number of former and current Supreme Court judges “who have indicated that they might be willing to offer training.”

Although they are priced similarly with other institutes in the market, Stoyles believes the courses offered from the CCIJ come “with the difference, and hopefully the very attractive feature, that for the same fee people are paying for other training, they’re actually supporting this really important charitable legal work for survivors of torture.”

The CCIJ’s aim to have about 60 to 70 participants in each course comes from the realization that there’s “a market” for “continuing professional development in the legal industry.” After conducting preliminary calculations, Stoyles predicts that within five years the institute can draw in between $100,000 to $800,000 in revenue annually.

“We’ve really done our homework,” says Stoyles, who says plans for the institute have been underway for two years.

“I know they’ve gone through many iterations to come up with the right business model, and that perseverance is really a testament to their commitment to try and support their chartable purpose,” says Jonathan Wade, co-ordinator for Ottawa’s Collaborative for Innovative Social Enterprise Development, who over the years, has provided the CCIJ with business support and grants.

Stoyles says the idea for naming the institute after Justice Kirsch came from a combination of his work with the CCIJ and his notable accomplishments dealing with international law. As a member of the CCIJ’s honorary council, Kirsch will serve as a member on the institute’s advisory committee.

Kirsch has chaired negotiations to establish the International Criminal Court in the Hague. He was elected as one of the first ICC judges, as well as the court’s first president. He is a former Canadian ambassador, and has held other high-level posts within the Department of Foreign Affairs.

Taught by members of the legal community, the Philippe Kirsch Institute will offer legal professionals courses to advance their knowledge of international justice. All proceeds of the program will go directly towards the organization’s charity, which helps victims of torture and war crimes seek justice.

Taught by members of the legal community, the Philippe Kirsch Institute will offer legal professionals courses to advance their knowledge of international justice. All proceeds of the program will go directly towards the organization’s charity, which helps victims of torture and war crimes seek justice. Named after internationally recognized Quebec jurist Philippe Kirsch, the institute is scheduled to be up-and-running within the year, and enable legal professionals to apply the CCIJ’s knowledge of international justice to other areas of the Canadian legal system.

According to Jayne Stoyles, executive director of the CCIJ, the institute was designed to serve a “dual purpose” of providing “legal training to the legal community” as well as utilizing the proceeds raised “to fund the CCIJ’s charitable legal work.”

Often referred to a “social enterprise,” this relatively new business model has been called “innovative” by professionals from the CCIJ’s ability to draw a profit for their social mission.

“It is a really challenging time for charities in Canada, and we’re just finding that our services are overstretching our resources and we don’t want to have to turn anyone away, so we decided to get really creative,” says Stoyles, who adds the idea to create the institute came after the CCIJ began to offer courses on international justice in 2000. “Rather than going as one more charity asking for donations, we thought that we could actually offer our expertise and make some of our own revenue.”

Kirsch is thrilled to be part of the initiative.

“CCIJ has an important mandate to fulfill, serving some of the hundreds of thousands of survivors of atrocities currently in Canada, while contributing to the global effort to send a message to would-be torturers and war criminals that they will face justice,” he says. “The business plan for the training institute has been very carefully prepared, and it is my strong expectation that the training will be highly sought after. This will provide a great service to the legal community in Canada, at the same time that it assists CCIJ in achieving its goals over the long term.”

Stoyles predicts there will be about 30 instructors for the planned 10 courses offered to prospective participants, which will have similar rates to other professional development courses in the market.

Courses are planned to teach participants how international law applies to Canadian legislation, and will include subjects involving civil litigation, immigration refugee law, criminal defence and criminal prosecution. Other planned areas of training include: how to provide services to torture survivors, and how to bring a case before an international body.

Taught by lawyers and judges involved in the CCIJ, including Kirsch, Stoyles promises the courses will provide “very high quality training” with the CCIJ having a number of former and current Supreme Court judges “who have indicated that they might be willing to offer training.”

Although they are priced similarly with other institutes in the market, Stoyles believes the courses offered from the CCIJ come “with the difference, and hopefully the very attractive feature, that for the same fee people are paying for other training, they’re actually supporting this really important charitable legal work for survivors of torture.”

The CCIJ’s aim to have about 60 to 70 participants in each course comes from the realization that there’s “a market” for “continuing professional development in the legal industry.” After conducting preliminary calculations, Stoyles predicts that within five years the institute can draw in between $100,000 to $800,000 in revenue annually.

“We’ve really done our homework,” says Stoyles, who says plans for the institute have been underway for two years.

“I know they’ve gone through many iterations to come up with the right business model, and that perseverance is really a testament to their commitment to try and support their chartable purpose,” says Jonathan Wade, co-ordinator for Ottawa’s Collaborative for Innovative Social Enterprise Development, who over the years, has provided the CCIJ with business support and grants.

Stoyles says the idea for naming the institute after Justice Kirsch came from a combination of his work with the CCIJ and his notable accomplishments dealing with international law. As a member of the CCIJ’s honorary council, Kirsch will serve as a member on the institute’s advisory committee.

Kirsch has chaired negotiations to establish the International Criminal Court in the Hague. He was elected as one of the first ICC judges, as well as the court’s first president. He is a former Canadian ambassador, and has held other high-level posts within the Department of Foreign Affairs.