Aboriginal people are not entitled to special consideration by the Crown in the exercise of prosecutorial discretion. So ruled the Supreme Court of Canada today in R. v. Anderson, overturning a decision by the Supreme Court of Newfoundland and Labrador.

The appeal stems from a drunk-driving case where the prosecutor sought a mandatory minimum sentence of 120 days for the accused, who had four prior convictions for impaired driving.

The appeal stems from a drunk-driving case where the prosecutor sought a mandatory minimum sentence of 120 days for the accused, who had four prior convictions for impaired driving.

The trial judge, however, denied the Crown a mandatory sentence, concluding the prosecutor failed to consider the Aboriginal status of the accused. That failure, the trial judge noted, rendered the mandatory minimum sentence disproportionate under the Charter.

The SCC, however — in a unanimous decision written by Justice Michael Moldaver — made clear the constitutional obligation to weigh proportionality rests with the court, not the prosecutor:

“The proportionality principle requires judges to consider systemic and background factors, including Aboriginal status, which may bear on the culpability of the offender. There is no basis in law to support equating the distinct roles of the judge and the prosecutor in the sentencing process.”

Requiring the Crown to weigh proportionality, the court says, “would greatly expand the scope of judicial review of discretionary decisions made by prosecutors and put at risk the adversarial nature of our criminal justice system by inviting judicial oversight of the numerous decisions that Crown prosecutors make on a daily basis.”

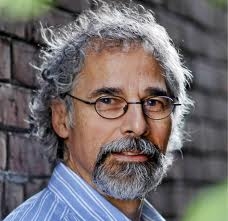

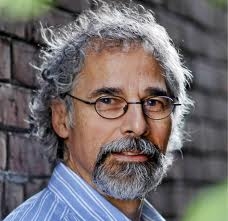

Jonathan Rudin is the program director and founder of Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto, which was an intervener in the case. He says the court’s ruling is frustrating in that it fails to define the scope of protections afforded Aboriginals from systemic discrimination.

“The difficulty is that the Supreme Court has said on a number of occasions that Aboriginal people face systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system,” says Rudin, “and this case doesn't really let us figure out how we're going to deal with that question.

“To what extent does Aboriginal overrepresentation [in the criminal justice system] in and of itself show discrimination? In other words, the fact that aboriginals are overrepresented, does that mean that it's always systemic discrimination? . . . I think that's where the next set of battlegrounds are going to be.”

One thing is clear, though: the court has put the kibosh on any line of attack against prosecutorial discretion in seeking mandatory minimums. Rather, says Rudin, if defence counsel want to challenge the proportionality of mandatory minimum, they are going to have to bring a Charter challenge directly — a far more daunting task.

“What you need to do is not attack the exercise of Crown discretion, but the sentencing regime itself,” he says. “So you have to challenge those laws constitutionally. And I think you're going to see more of that.”

The appeal stems from a drunk-driving case where the prosecutor sought a mandatory minimum sentence of 120 days for the accused, who had four prior convictions for impaired driving.

The appeal stems from a drunk-driving case where the prosecutor sought a mandatory minimum sentence of 120 days for the accused, who had four prior convictions for impaired driving.The trial judge, however, denied the Crown a mandatory sentence, concluding the prosecutor failed to consider the Aboriginal status of the accused. That failure, the trial judge noted, rendered the mandatory minimum sentence disproportionate under the Charter.

The SCC, however — in a unanimous decision written by Justice Michael Moldaver — made clear the constitutional obligation to weigh proportionality rests with the court, not the prosecutor:

“The proportionality principle requires judges to consider systemic and background factors, including Aboriginal status, which may bear on the culpability of the offender. There is no basis in law to support equating the distinct roles of the judge and the prosecutor in the sentencing process.”

Requiring the Crown to weigh proportionality, the court says, “would greatly expand the scope of judicial review of discretionary decisions made by prosecutors and put at risk the adversarial nature of our criminal justice system by inviting judicial oversight of the numerous decisions that Crown prosecutors make on a daily basis.”

Jonathan Rudin is the program director and founder of Aboriginal Legal Services of Toronto, which was an intervener in the case. He says the court’s ruling is frustrating in that it fails to define the scope of protections afforded Aboriginals from systemic discrimination.

“The difficulty is that the Supreme Court has said on a number of occasions that Aboriginal people face systemic discrimination in the criminal justice system,” says Rudin, “and this case doesn't really let us figure out how we're going to deal with that question.

“To what extent does Aboriginal overrepresentation [in the criminal justice system] in and of itself show discrimination? In other words, the fact that aboriginals are overrepresented, does that mean that it's always systemic discrimination? . . . I think that's where the next set of battlegrounds are going to be.”

One thing is clear, though: the court has put the kibosh on any line of attack against prosecutorial discretion in seeking mandatory minimums. Rather, says Rudin, if defence counsel want to challenge the proportionality of mandatory minimum, they are going to have to bring a Charter challenge directly — a far more daunting task.

“What you need to do is not attack the exercise of Crown discretion, but the sentencing regime itself,” he says. “So you have to challenge those laws constitutionally. And I think you're going to see more of that.”