Strathy says the court has made strides on diversity and using technology

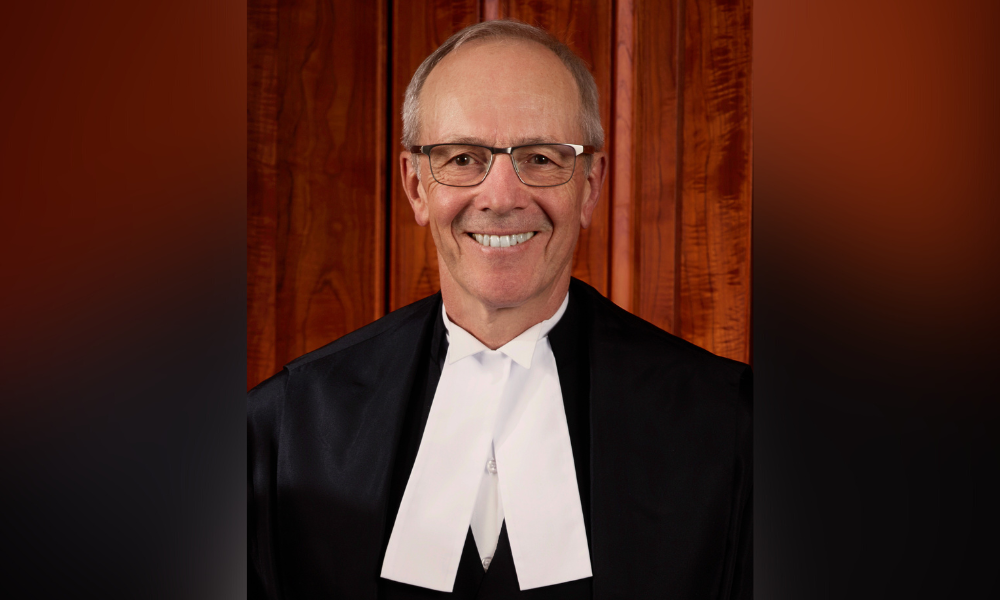

Canadian Lawyer recently spoke with Chief Justice George Strathy, who announced he would retire as Chief Justice of Ontario and President of the Court of Appeal for Ontario this month. Strathy outlined some of his achievements leading Ontario’s top court and what he plans to do after leaving the court.

Why did you choose to retire before your mandatory retirement date?

I never liked the idea of walking around with my “best before” date stamped on my forehead. I concluded now, which is about 11 months before my mandatory date, made sense.

I think the Court of Appeal is in a good place. We have our full complement of judges. We've come through the pandemic without any meaningful backlog in our work. Our infrastructure is strong, and there are many good candidates to take over from me.

So, the stars aligned, and it seemed like a good time.

Tell me about the court’s transition into the digital age

Four years ago, we initiated an upgrade to the court’s technology. I always felt that our current system worked well enough, but it was about 25 years old. It was not particularly user-friendly.

So, we signed a contract about three years ago with Thomson Reuters to upgrade our system. We'll be moving to e-filing in about a year.

Once you move to digital technology, the challenge was always getting judges and lawyers attuned to using digital materials. The pandemic solved that problem. The transition was almost like switching on a light. We're not going back to paper. There's no reason to.

The contract with Thomson Reuters came at the right time.

The timing is quite fortuitous. The acceptance of technology is already there because of the pandemic. We won't have to prepare our judges and staff for the change.

What's your general feeling about what proceedings will stay virtual?

For virtual proceedings, we'll do case conferences, or what we call appeal management conferences. We will do short attendances for what we call status court. It's convenient for litigants and counsel.

I see the benefit of in-person attendance for longer appeals. But two years of remote work has shown courts can conduct remote hearings well and fairly.

We haven't established any firm rules on how we determine whether a proceeding will be virtual or in person yet, and we'll probably wait to see how things develop.

Does the virtual versus in-person debate play out differently at the trial level?

I wouldn't want to speak on behalf of the trial courts or what they can do now.

I can say that some witnesses don’t have to give their evidence in the courtroom. But there are probably other witnesses where one party and maybe the judge would say, “I want to see that witness in court. Their credibility is important.”

What is clear is that the courts can and will be able to deal more efficiently with the evidence of some witnesses through remote hearings.

What advice will you be giving to the new chief justice?

I've met many people involved in the overall justice system, including lawyers, judges, and leaders of various legal organizations and groups affected by the justice system.

I would say to my successor, get to know the people impacted by the administration of justice and learn. But every chief justice defines the role they want to play in the system. There is no comprehensive job description for the position. The job description in the Courts of Justice Act doesn't say a fraction of what the job is or can be.

You have spoken out on inequality and systemic discrimination – do you feel it was risky to do so as a judge?

There is a risk in judges speaking out on public issues. And the risk is that they will be perceived as having taken a position on matters that could come before a court.

However, where I've spoken out about issues of race, for example, or inequalities in society, these are issues on which the courts have already spoken. Our court has recognized the persistence of systemic racism in our society. That is not debatable. The same thing applies to economic disparity.

I see it as part of my job to highlight those issues because they affect the administration of justice and to urge change in how our courts and the bar deal with them.

You have proactively reached out to equity-seeking groups – how do you think the judiciary can best do that?

We set up a working group of judges and representatives of various diversity organizations. It has a wide range of diversity organizations that help educate, inform and sensitize the bench to their concerns and those of their clients.

It's a bit of a two-way street, but we're mostly the beneficiaries on the court.

What kinds of initiatives have come out of these discussions?

The groups indicated that some of their racialized members, particularly their more junior members, have challenges in their advocacy before judges. So, the Court of Appeal developed a program with the Advocates’ Society, where they train young barristers from racialized backgrounds.

We're looking at other things, including a course that will be held with Crown Attorneys to train young criminal advocates.

We're having ongoing discussions with the diversity group about training for judges, primarily related to racial bias.

You have encouraged the participation of junior counsel in oral argument – tell me why.

Mentoring is the ongoing concern of young lawyers at all levels and locations. It only worsened during the pandemic when it was all business. Mentoring seems to have fallen by the wayside.

I put up a notice to the profession during the pandemic, saying that counsel are encouraged to permit junior counsel to have part of the argument on the appeal. We've had terrific, positive feedback from that.

Beyond that, I think the issue of mentoring is a particularly serious issue for the many young lawyers practising either on their own or in small firms. I know that the Law Society of Ontario has a mentoring program. The Ontario Bar Association and the Advocates’ Society are looking at these things. But we must do more.

Your article on mental health received a lot of attention. Why do you think it resonated?

Almost every day, I get a letter or a note from someone saying that they're grateful for it, pointing to their concerns in the area or referring to someone they know who's had a concern or how it's been dealt with.

I think the reason it resonates with people is they're feeling the stress. They were feeling the stress before COVID, and it only worsened.

The one thing I know I am going to do after my retirement is to continue to pursue this issue. What I am looking at now is the question of what is next. We need a top-down change in the profession and a top-down approach to mental health.

In other areas, we have demonstrated what the bar can do when we put our minds to it. It's not over yet, but if you look at the issue of racism and anti-racism training, the bar has started to address that in a meaningful way. Some leading firms have appointed chief diversity officers and taken the issue seriously. We might look at doing similar things in the area of mental health.

Why did you choose to speak to the profession about mental health?

Initially, I spoke at a symposium on mental health about my mother's mental health challenges and published the paper you referred to.

At the time, I had never spoken publicly or privately about my mother, who had what was then called manic depression and is now called bipolar illness. That started me on the path to learning more about mental health and its stigma and challenges.

Are there any other issues you want to highlight to the legal profession, legislators and other law firm leaders?

Our province has an extraordinary justice system, maybe one of the strongest and best in the world. That comes from the broad range of people and organizations working with the system to make it strong.

But we can make it better. The number one way we can improve it is to provide better funding for legal aid and pro bono.

Thousands of lawyers across the province already do pro bono work. And there are pro bono organizations willing to link those lawyers with deserving litigants who can't afford to come before the courts or represent themselves. And all those organizations need is funding to help them administer their programs.

The threshold to obtain legal aid is below the poverty line. We could save the system millions of dollars annually by addressing that and ensuring more people get adequate representation.

It's a false economy to deny funding to people who are just above the current threshold. Funding legal aid better would create savings that would more than make up for the difference.

*Answers have been edited for length and clarity.